by Bob Cowan

In the centre of the photo above is Fingask Castle, near Rait in Perthshire. The castle dates from 1594. It remains a family home and is a romantic venue these days for weddings,

see here. You can read about the castle's history

here and

here.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, Fingask was home to Sir Patrick Murray Threipland, the fifth baronet. Sir Peter, as he was called, was head of the household with three older sisters, Jessie, Eliza and Catherine, all unmarried, and their mother, Lady Murray Threipland.

The census in March 1851 shows that the Threipland family had a staff of seven: a housekeeper (Jean

Oswald); a ladies maid (Mary Gray); a cook (Margaret Stewart); Sir Peter's own housemaid (Mary McLagan); a butler (David Chalmers); a footman (John

Bertram); and a coachman (Andrew David).

The Fingask Curling Club was founded in 1843 and admitted to the

Royal Caledonian Curling Club the same year. Sir Peter was the driving force. The club's membership, as

at November 1, 1849, is recorded in the

Royal Caledonian Curling Club Annual for 1849-50.

Sir Peter was the President, and his mother, Lady Murray Threipland,

was the 'Patroness'. David Chalmers, a regular member since 1844, was also on the

club's management committee. There were nineteen regular members, and

six occasional members. The club even had an 'Extraordinary Member',

James Young, 'Civil Engineer to the Club'.

David Chalmers was Sir Peter's butler. In 1851 Sir Peter was fifty years old, and David thirty years of age. David kept a record of his

activities at the castle and this has survived. A booklet,

The Butler's Day Book 1849 - 1855, is the

source of the information here. It's subtitled

'Everyday Life in a

Scottish Castle'. It is a collection of short diary entries and was privately published by Andrew Threipland in 1999.

This my own copy of

The Butler's Day Book, with its image of Fingask Castle on the somewhat faded front cover.

Curling gets many mentions and the entries clearly show that the sport played a significant role in everyday life at Fingask in the winter

months. Over five winters from 1849 to 1855, David records playing on the Fingask pond(s) on over one hundred occasions. The winter of 1850-51 was poor, with only six days play that he mentions. But in the other years, it seems that ice could be found regularly from December through February, and occasionally in November and March.

Typical entries are that of December 24, 1849, "Sir P. and I curling all day," or January 5, 1850, "Sir P. and I went to the curling and had a fine game." Two days later there was, "A fine turn out of curlers and fine ice."

The pond was inspected often in the hope that play would be possible, for example, on December 4, 1852, "Sir P., Robertson and I went to the pond but the ice would not do." So David went shooting pigeons that day. Four days later, "I and Charlie went up to the curling pond and had a fine game."

January 19, 1853, "Sir P., Robertson and I curling. Ice very watery today." The following day, "Ice all gone."

March 10, 1855. "Began curling this morning at 6 o'clock and gave it up at 10 o'clock. Came on a heavy fall of snow."

Curling went on even if conditions were not perfect. January 21, 1854, "Sir P. and I curling. Came on rain. Sir P. left us and went home for the wet. I stopped and had a fine game."

It was not uncommon to play all day. But perhaps March 4, 1852, was exceptional, "Sir P. went to the curling after breakfast, the rest of us started early in the morning. Fine ice till 10 o'clock pm."

Where were these games taking place?

At the time that David was recording his curling exploits, the Fingask curlers had two ponds, both to the north west of Fingask Castle itself. These are clearly marked on the Ordnance Survey map published in 1867, although surveyed several years earlier. Play on the 'upper pond' is recorded occasionally in

The Butler's Day Book. But mostly play was on the 'lower pond', that shown in the bottom of the image above, nearer the castle than the other.

The

Royal Caledonian Curling Club Annual for 1853-54 records the following in an article about artificial ponds. "The Fingask Pond, which was made by that distinguished landlord and keen Curler, Sir P. M. Threipland, is in many respects similar, with this advantage, however, that it is 6 or 700 feet above the level of the sea, which will insure ice at an earlier and much later season of the year than in any other Curling Pond in the kingdom."

This refers to the 'lower pond'. We know from

The Butler's Day Book that there was a curling house beside the pond, for example, January 1, 1854, "The curling lodge broke into last night and some Aqua taken out of it." Evidently, it was used for post-game refreshments! It was also big enough to host meetings of the club, for example, August 28, 1855, "Sir P. at a meeting at the curling bothy of the curlers. A good turn out."

Indeed, a building is evident on the old maps. The curling house (or lodge, or bothy) is the pink square on the north side of the pond in this clipping from the OS 25 inch map of 1867.

The pond had to be maintained. On August 30, 1852, David records, "Thomas Mitchell repairing it." On December 7, 1853, "A new rope put on the flag staff at the curling pond."

February 17, 1853, was a special day on the Fingask pond. "Sir P. curling. Lady Threipland's medal played for today. Gained by the secretary Mr. Morrison, took it at 7 points. The Miss Threiplands all up and a fine turn out of ladies. Had a splendid luncheon sent up to the pond from the castle. Everyone very happy and all had a fine dancing on the green after luncheon in which the ladies and onlookers took great delight in. But the curlers set to work again to play for other two prizes and very sorry they were that Mr. John Frost would not allow them to get their feet shaken. The Misses Threipland gave a very handsome curling vest to be played for. It was all wrought over with curling stones and besoms all though it. Everyone eager to get it and especially the bachelors. And Sir P. gave a pair of curling stones to be played for at the same time and after the points was all played and the books added up Mr. Sprunt counted 7 points, and Mr. Scott 6 points, the two highest. Mr. Sprunt got the vest and Mr. Scott the stones, both married men. Bachelors far back."

Lady Treipland's medal was the Fingask Club's premier competition for singles play 'at points'.

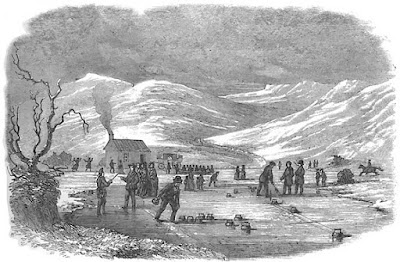

That day in February 1853 was the subject of an article about curling which appeared in the

Illustrated London News on January 7, 1854. This was accompanied by an engraving of the scene - it would be fifty years before photographs of curling appeared in newspapers. The image shows the curling house, with smoke coming from the chimney, and the hills behind. There are people dancing outside. A coach is drawn up at the door. A group of three ladies is seen standing on the ice. The play looks odd - but the artist is trying to show that it is not team vs team curling that is going on, but points play. The odd looking handles on the stones perhaps suggest that the engraver, in copying an artist's sketch, had not himself ever seen an actual curling stone!

Whatever the flaws, the newspaper image conveys the excitement of the occasion and brings the day to life. One can only imagine though just what the prize 'curling vest' was like.

The Fingask Club competed against neighbouring clubs, sometimes on their own pond, and sometimes elsewhere. The Fingask pond was used as a neutral venue when neighbouring clubs competed for a Royal Club District Medal. And Fingask Curling Club was represented by three rinks at the 1853 Grand Match, the first to be held at the Royal Club's new pond at Carsebreck. All these events were recorded by David Chalmers in

The Butler's Day Book.

On December 31, 1852, he records the purchase of baskets for his curling stones. "Paid 8/6d for them." (That would be around £40 today.)

There are many entries that leave the reader wanting more information! On

March 10, 1849, David writes "Me and Willie went up to the curling pond about 2 o'clock

but got no curling. Mr Souter and two or three more there drinking

toddy. Mr Souter and some of the rest fell out and had a regular sprawl.

I kept free of them."

One has to wonder what the stramash was about. The 'Mr Souter'

is undoubtedly Andrew Souter, who had been a regular member since the

Fingask club was formed. Indeed, he had even been on the management

committee in 1846. For whatever reason, Souter is not listed as a member

of the club after 1849, nor is he mentioned again by David Chalmers in

The Butler's Day Book.

On August 1849, David records, "Sir P and I went up to the curling

pond and brought down our curling stones to get polished. Willie went

into Perth to the Court about a ferret and gained the day." What was the story about the ferret, I wonder?

The last mention of curling in

The Butler's Day Book is dated December 31, 1855. This says, "A very dull day and very fresh. There has been a great deal of curling this year but the Fingask Club, I am sorry to say, has been very unlucky in all their matches, always beat, very bad."

Sir Peter died in 1882 aged 81, but not before he had constructed an artificial pond within the castle's grounds. The ponds on the hill fell into disuse. David Chalmers remained as Sir Peter's butler. He was sixty years old at the 1881 census, and presumably was at Sir Peter's side when he died. He continued to be a member of the Fingask CC long after the records in

The Butler's Day Book finished. He even won Lady Murray Streipland's medal in 1867, as recorded in the

Dundee Courier on February 1 that year. His name is

listed on the Fingask club's roster of members as at October 1891, although just as an 'occasional member'. In fact, he died in November of that year, aged 70.

The Fingask Curling Club is still in existence today.

There is one last curling connection which can be made from entries in

The Butler's Day Book. On August 14, 1850, David records, "Mr Rees, portrait painter, arrived here to take Sir Peter's likeness for a painting he is painting of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club." The 'Mr Rees' was in fact Charles Lees, well known for his painting of 'The Golfers' (

see here) from 1847. Lees was now working on a painting to commemorate the Grand Match at Linlithgow Loch. He stayed at Fingask until August 16.

The Linlithgow Grand Match had taken place on January 25, 1848.

Thirty-five northern rinks played an equal number of southern rinks,

with a further hundred southern rinks playing matches amongst

themselves. Charles Lees's large painting includes images of various notable curling personalities of the time, even those who were not present at the Grand Match. It is believed that Lees travelled to the homes of curlers to

sketch those to be included.

The Butler's Day Book contains the evidence that he did.

After years in private hands, the painting was bought by the Royal Caledonian Curling Club in 1898 and has belonged to the curlers of Scotland since then. It's a long story but, happy to say, the painting has recently been restored and is now on loan to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and is on display in Edinburgh,

see here. Sir Peter is highlighted in the detail from the painting above.

Lastly, it should be said that

The Butler's Day Book contains much of interest other than curling! There are copies in the National Library of Scotland if you want to read it for yourself.

Top photo: Fingask Castle from the air, taken from a hot air balloon just east of Rait. The image is © Mike Pennington and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence. It is from the Geograph website here.

The map images are courtesy of the National Library of Scotland, and are screenshots from maps on the library's maps website here. If you want to find out more about historical curling places, go here.

The image from the Illustrated London News has been widely reproduced and can be easily found on the Web.

The detail from Grand Match at Linlithgow is from an old reproduction of the painting in my collection of memorabilia. As noted above the original is owned by the Royal Caledonian Curling Club and is currently on display at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Queen Street, Edinburgh.